The Endurance

| Builder | Framnaes Mek, Verstad, Sandefjord, Norway |

|---|---|

| Launched | 1912 |

| Type | Barquentine / 1 funnel, 3 masts |

| Length | 43.9m |

| Beam | 7.5m |

| Expedition | Imperial Trans-Antarctic (Endurance) Expedition (1914 1917) |

| Led by | Sir Ernest Shackleton |

Sir Ernest Shackleton Imperial Trans-Antarctic (Endurance) Expedition (1914-1917)

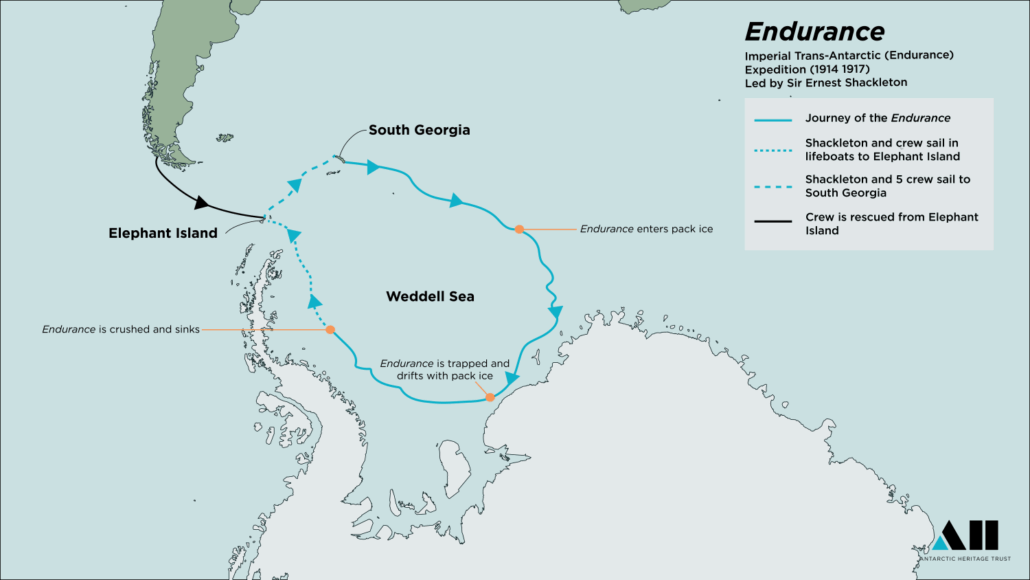

In 1914, Sir Ernest Shackleton launched his most ambitious Antarctic expedition yet — a bold attempt to cross the entire continent from coast to coast via the South Pole. The vessel chosen for the journey was Endurance, a Norwegian-built barquentine originally intended for Arctic tourism. The expedition would become one of the greatest survival stories in the history of exploration.

Built with a thick hull of oak and greenheart, she was widely considered one of the strongest wooden ships ever constructed. Shackleton purchased her for £11,600. Though he had wanted to use the name Endurance on his previous expedition, it had remained Nimrod. Now, the ship would carry the name drawn from Shackleton’s family motto: Fortitudine Vincimus — by endurance we conquer.

Endurance sailed from Plymouth on 8 August 1914 without Shackleton on board. He later joined the crew in Buenos Aires on 26 October. During this leg of the journey, a young Welsh stowaway named Percy Blackborow was discovered. Shackleton initially reprimanded him but soon allowed him to stay. Blackborow quickly proved himself a capable and hardworking member of the crew.

Shackleton took swift command of the situation in Buenos Aires. He dismissed unruly crew members and reorganised the ranks, restoring discipline. Frank Wild arrived with the sledge dogs, bringing a noisy energy to the voyage but lifting spirits with their presence.

After crossing the South Atlantic, Endurance reached South Georgia on 5 November 1914. The crew received a warm welcome from the 2,000 Norwegian whalers at Grytviken, who shared their knowledge of ice conditions. The warnings were grave, it was a severe season for sea ice. Shackleton delayed departure longer than planned, waiting for the best possible conditions.

The expedition resumed on 5 December. On 8 December, they sighted the first pack ice at 57 degrees south. As the crew pushed east into the Weddell Sea, the scale of the challenge became clear. Endurance was 600 miles from the nearest known landfall, though that particular coast would remain undiscovered for another fifteen years. The crew was nearly 1,000 miles from their intended destination at Vahsel Bay.

The ship pressed on, battling slow-moving pack ice that alternately loosened and re-formed. On 10 January 1915, land was spotted at 72°2′ south — the ice front of Coats Land, discovered in 1902. Spirits rose. With good sailing conditions and calm seas, the men believed they were nearing their goal.

But on 18 January, just 80 miles from Vahsel Bay, the ice closed in again at 76°30’S, 31°30’W. For a time they drifted within a frozen sea. By 21 February, Endurance had reached her furthest south at 76°58’S before being carried north again by ice movement. The ship had travelled over 12,000 miles since leaving England, including more than 1,000 miles through the pack ice. Yet they were now adrift, trapped just 60 miles from their destination.

Shackleton prepared his men for a winter in the ice. Disappointment ran deep, but he maintained morale. The dogs were offloaded onto the ice and organised into sledging teams, although few of the men had any experience with dog driving. Supplies were spread across the floe, while the ship remained the main shelter.

On 14 July, carpenter Harry McNeish heard ominous sounds from beneath the stern. Shackleton initially suggested it was a whale, but McNeish recognised it as ice movement. Endurance had been built for strength, but she lacked the rounded hull of other ice ships such as Fram, which would rise above ice pressure. Instead, Endurance would resist the ice with brute force.

Through August, the ship remained locked fast. Then in early September, renewed pressure caused beams to buckle and seams to open. The hull twisted and strained. Shackleton remained optimistic, even ordering a new wheelhouse to be built in case the ship floated free.

On 15 October, Endurance briefly broke free into a narrow channel. Two days later, the ice surged again and the ship was violently heaved to a 30-degree list before slowly righting herself. The men raised steam, hopeful for escape.

By 23 October, McNeish had constructed a cofferdam to contain flooding in the engine room. Pumps worked continuously, but water kept rising. The hull was now weakened, sitting lower than ever before. Any new pressure would grip her more firmly.

On 25 October, the situation became critical. The ice squeezed both sides of the ship and the stern, and the crew abandoned attempts to save her. Two days later, Shackleton ordered all hands to the ice. At 5pm on 27 October 1915, the men assembled for their final meal aboard. In silence, they ate their supper in the wardroom, then stepped out into the Antarctic twilight.

The wreck of Endurance remained visible for nearly a month, allowing time to salvage vital supplies. On 21 November, the wreck gave a final lurch and disappeared beneath the surface. The men now stood alone on a drifting floe, more than 1,200 miles from safety.

After five months camped on the ice, the floe began to break apart. On 9 April 1916, the crew launched three open lifeboats — the James Caird, Stancomb Wills, and Dudley Docker — and made a harrowing five-day journey to Elephant Island, landing on 15 April. It was the first solid ground they had stood on in nearly 500 days. But it was remote, uninhabited, and far from any hope of rescue.

Shackleton resolved to sail for help. On 24 April, he set off with five men — Frank Worsley, Tom Crean, Harry McNeish, Tim McCarthy, and John Vincent — in the James Caird, a 6.9 metre lifeboat modified for open ocean. Over 16 days they crossed 800 miles of the wildest seas on Earth. Worsley’s precise navigation brought them to the south coast of South Georgia on 8 May.

Unable to reach the whaling stations by sea, Shackleton, Worsley, and Crean crossed the island’s uncharted interior on foot. After 36 hours of nonstop travel across glaciers and mountains, they reached Stromness whaling station on 20 May.

The remaining three men were rescued from the other side of the island. But repeated attempts to reach Elephant Island failed due to ice and weather. Finally, on 30 August 1916, Shackleton returned aboard the Yelcho, a Chilean vessel. All 22 men were alive. Not a single life had been lost.

Their survival remains one of the most extraordinary stories of endurance and leadership ever recorded.

Endurance Found

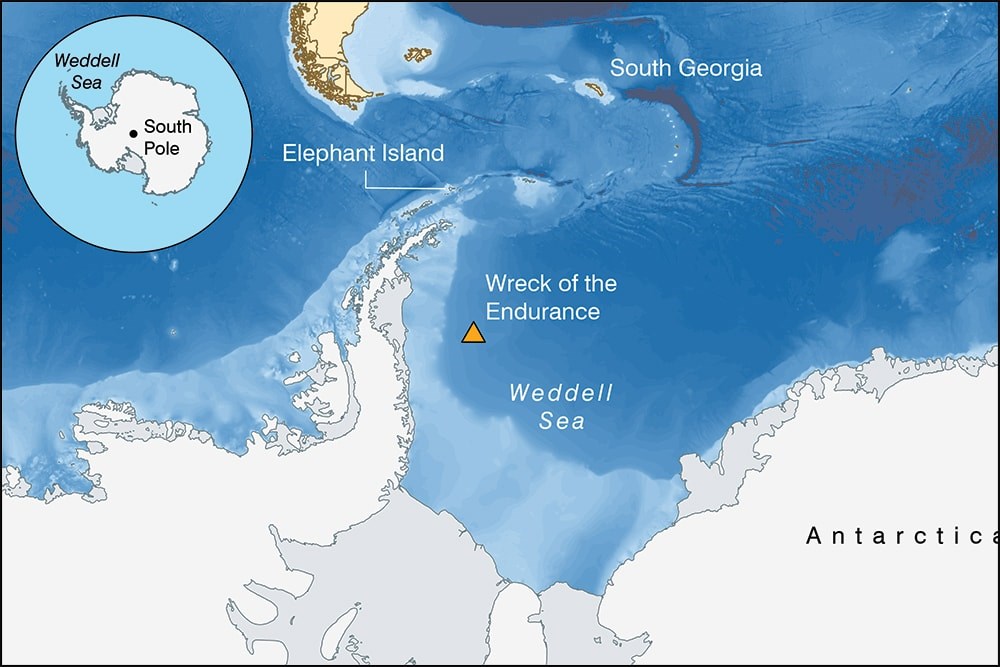

In March 2022, the Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust’s Endurance 22 Expedition successfully located the wreck of Sir Ernest Shackleton’s lost ship Endurance.

Crushed by ice in the Weddell Sea, Endurance sunk in 1915, and sparked an incredible tale of survival. Previous attempts to unearth the ship have been thwarted by heavy sea ice, including the loss of a remote search vehicle. This is a landmark find from one of the most remarkable stories of the heroic age of Antarctic exploration and was fitting it was found in the centenary year of Sir Ernest Shackleton’s passing.

UKAHT & Endurance: Conservation Management Plan

In July 2024, the UK Antarctic Heritage Trust (UKAHT) published a comprehensive Conservation Management Plan (CMP) for the wreck of Sir Ernest Shackleton’s Endurance.

Led by UKAHT, in partnership with Historic England, the CMP acts as a shared vision and framework to inspire an international effort to protect and promote understanding of Endurance, for current and future generations.

A key objective of the CMP is to ensure the preservation of the wreck in situ. Although the wreck is a designated historic monument (HSM) and its remote location in the Weddell Sea serves as a protective factor, with warming temperatures and sea ice loss, it could become increasingly vulnerable. Risk factors identified in the CMP include unauthorised visits using new subsea technologies (ROVs, AUVs and submersibles), tourist visits, commercial fishing and unauthorised recovery activity of artefacts.

Further Reading

The Endurance: Shackleton’s Legendary Antarctic Expedition

Caroline Alexander

First published November 8, 1998

Endurance: An Epic of Polar Adventure

Frank A. Worsley

First published January 1, 1931

Endurance: Shakleton’s Incredible Voyage

Alfred Lansing

First published January 1, 1959

Endurance (Documentary)

Chai Vasarhelyi, E., Chin, J., & Hewit, N. (Directors)

National Geographic Documentary Films

DisneyPlus

![]()

Antarctic Heritage Trust

7 Ron Guthrey Road, Christchurch 8053, New Zealand

Private Bag 4745, Christchurch 8140, New Zealand

© Copyright 2025, Antarctic Heritage Trust Registered Charity: CC24071

Terms and Conditions – Privacy Policy

![]()

Antarctic Heritage Trust

7 Ron Guthrey Road, Christchurch 8053, New Zealand

Private Bag 4745, Christchurch 8140, New Zealand

© Copyright 2025, Antarctic Heritage Trust Registered Charity: CC24071

Terms and Conditions – Privacy Policy