Sir Ernest Shackleton’s dream to cross the Antarctic continent had its origin in deep disappointment.

His attempt to be the first to snare the prize of the South Pole had ended in honourable defeat when, in 1909 he abandoned the pursuit and turned back only 97 nautical miles short of his goal.

Known as the finest decision in polar history it saved his team’s lives. Before Shackleton could mount another attempt, Roald Amundsen and Captain Robert Falcon Scott each succeeded in reaching the Pole. Scott and his polar party perished on their return.

What prize was left to be won?

Shackleton’s dream materialised with the idea of a trans-Antarctic expedition. Beginning in the Weddell Sea, passing through the South Pole and ending on the other side of the continent, in the Ross Sea, it would be the first crossing of the continent.

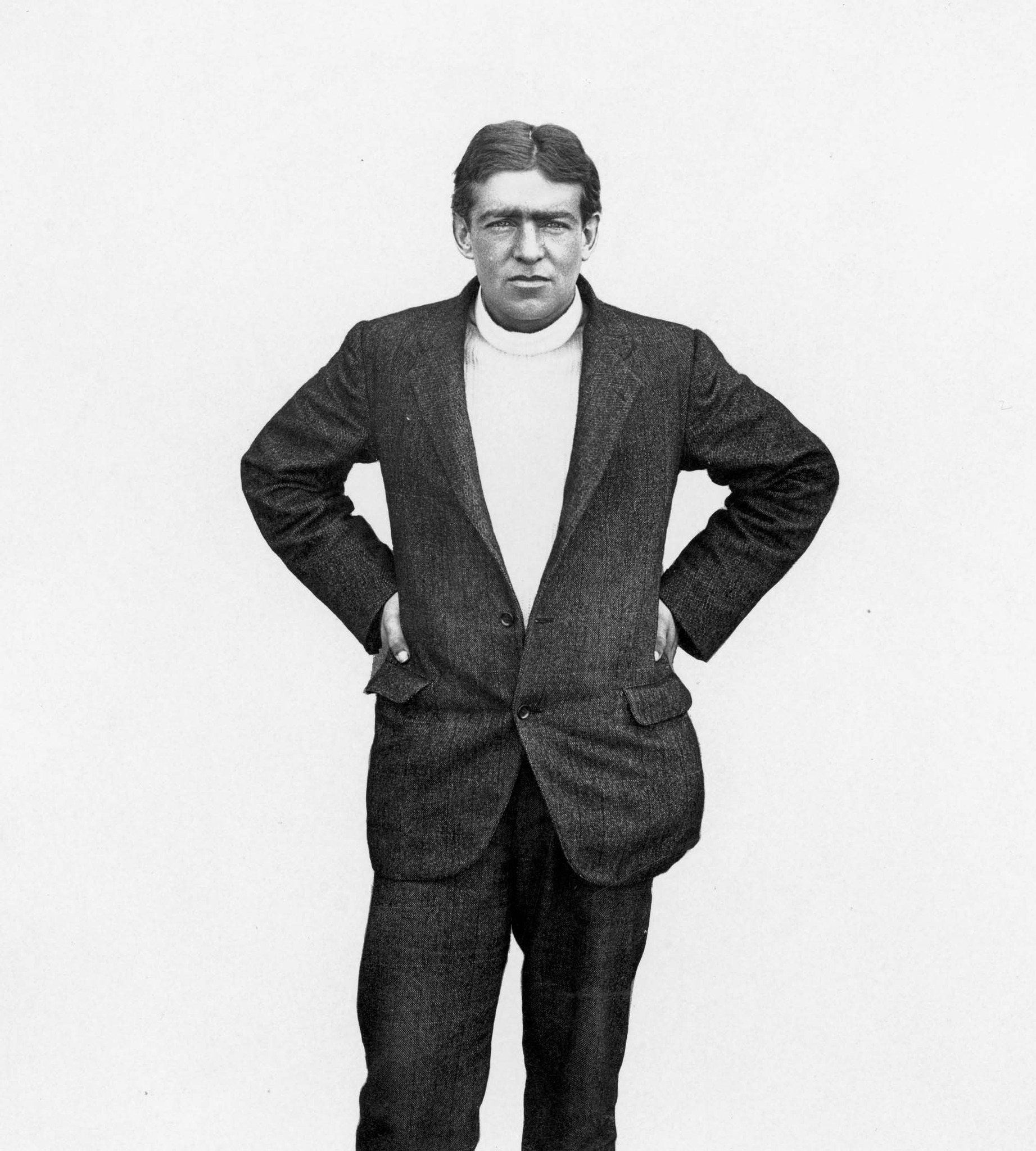

Sir Ernest Shackleton ©Canterbury Museum

It was an audacious plan, involving two ships and two teams. One team, led by Shackleton, would sail in the Endurance as far south into the Weddell Sea as the ice allowed. The aim was that Shackleton, with five men, 100 dogs and two motorised sledges with aerial propellers, would set out immediately with the hope that they might complete the 1800 mile journey, via the Pole, to the Ross Sea within five months.

Meanwhile the second ship, the Aurora, would land six men at the Ross Sea base. They were to push southward towards the top of the Beardmore Glacier, laying depots of food and fuel as they went and, all going well, await the arrival of those travelling from the Weddell Sea. This would enable Shackleton and his Trans-Continental Party to replenish supplies towards the latter stages of the journey and, it was hoped, gain the assistance of extra men during the last trudge to the Ross Sea.

Shackleton’s ship, the Endurance trapped in ice in the Weddell Sea ©Canterbury Museum

From the moment that he went public with his plans, he was inundated with keen applicants. From nearly 5,000 applications, Shackleton hand-picked a team of 56.

What followed was the world’s greatest adventure story.

After leaving South Georgia Island and heading deep into the Weddell Sea Endurance was stuck in the ice for 10 months over the dark Antarctic winter until she could handle the pressure no more.

On 21 November 1915 she finally succumbed to the pressure of the sea ice and sank into the depths of the Weddell Sea.

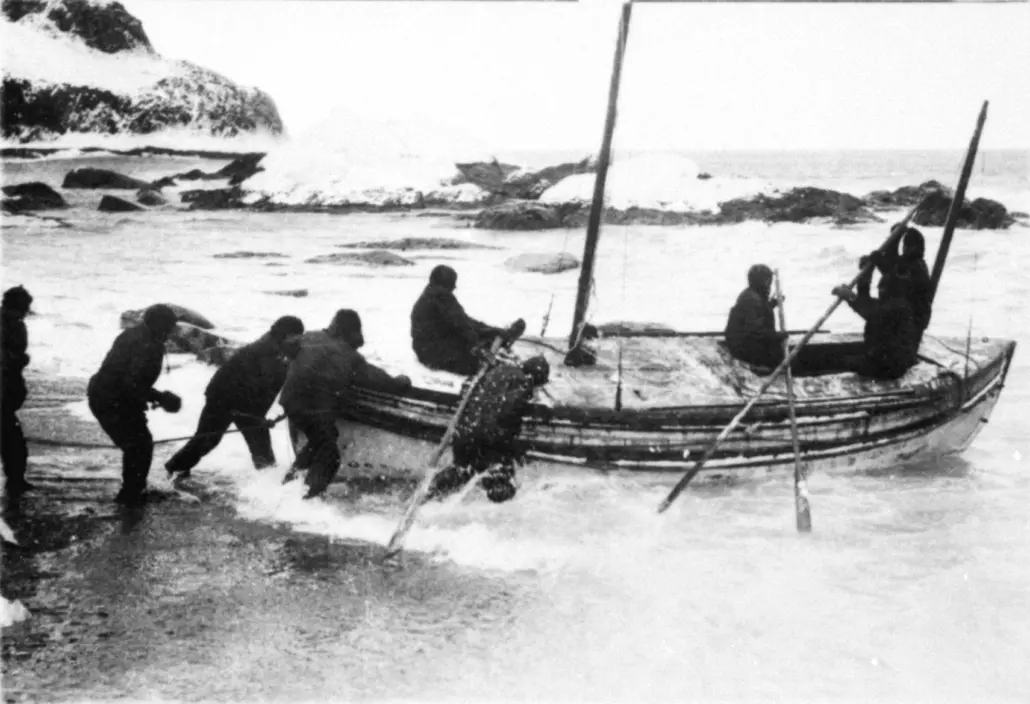

Following camps on the ice floes over nearly six months Shackleton and the crew took to the life boats and through rough conditions made their way to Elephant Island. From there Shackleton, Endurance Captain Frank Worsley and a team of four set out on a life boat across the roughest ocean in the world over 800 miles to reach South Georgia.

This journey has been described quite simply as the greatest small boat journey of all time.

The final chapter was an epic traverse of South Georgia Island. Shackleton, Worsley and Crean crossed the rugged, virgin interior of the island in one push and descended to safety to civilisation at Stromness Whaling Station to raise the alarm.

Back from the dead after 18 months, Shackleton’s story became legend.

The James Caird is launched from Elephant island ©Frank Hurley, Canterbury Museum

Endurance Found

In March 2022, the Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust’s Endurance 22 Expedition successfully located the wreck of Sir Ernest Shackleton’s lost ship Endurance. Trust alumnus James Blake was Director of Photography on the Endurance22 Expedition and was controlling the camera when the iconic footage of Endurance were captured.

Through the Trust, James has a special connection to Sir Ernest Shackleton’s legacy and the story of the Endurance. In January 2007 he visited Shackleton’s Nimrod hut at Cape Royds in Antarctica to launch the Trust’s Antarctic Youth Ambassador programme in partnership with Blake Trust and Antarctica New Zealand and was involved in the work to uncover Shackleton’s whisky.

In 2015, to honour the centenary of Shackleton’s crossing of South Georgia, James took part in the Trust’s inaugural Inspiring Explorers Expedition™ to retrace the epic crossing made by Shackleton, Worsley and Crean to raise the alarm and get help for the crew of the Endurance. He produced a film about the crossing called The Last 36.

The stern of the Endurance with the name and emblematic polestar. © Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust and National Geographic

Shackleton’s Hut, Cape Royds

Antarctic Heritage Trust cares for the expedition base in Antarctica associated with Sir Ernest Shackleton’s British Antarctic (Nimrod) Expedition 1907–1909, during which Shackleton attempted to be the first to reach the Geographic South Pole.

Shackleton’s Hut, Cape Royds, Antarctica © AHT